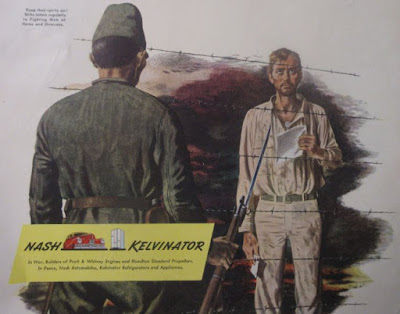

Their eyes lock with yours. That’s the first thing you notice, and the raw emotion of the background starts first from the face that is speaking to you and the eyes that make contact with you. It’s striking and even startling that you’re really looking at a magazine advertisement for a car company. The cars are not in the picture, because the company isn’t making them anymore.

It was World War II, and car companies, along with appliance and many other manufacturers had turned from making their regular products to producing material for the war effort. They were making tanks and planes now, uniforms, and all manner of military items. These could not be sold to the public, so they had nothing to sell. But they needed to keep their names in the public eye until the war was over. So ads were published to encourage buying bonds (and thereby saving for the day when they could buy a new car, which Americans did, in large number).

My favorite among those ads were the Nash-Kelvinator. Each one told a little story. It was first person, usually the rambling stream-of-consciousness thoughts of the main figure in the ad talking directly to the reader. The nurse who, in the midst of a frantic triage on a Pacific Island jungle discovered her own brother among the wounded.

The man who, lost at sea in a lifeboat talks to himself, encouraging himself to not give up – because he wants to return to marry his sweetheart and return to his job, and to an America where he is free and has opportunity to work.

The guy wounded in the jungle who is fading in and out of consciousness, bleeding on the stretcher, “Somehow, I never thought it would end this way. I never thought I’d go home like this.”

The hollow-eyed POW who finally got a letter from home. The guy standing on the train depot, just home from the war, not jubilant but wary, demanding direction – what happens now? Each of the narratives drops you into a story already in progress, and you never get to know the ending. You are left to imagine it and wonder, and that may be the best storytelling of all.

There is, of course, in all the ads the suggestion that manufacturing is a big part of our war effort and therefore is a big part of American democracy. We hear about the rights of a man to return to a job and rise according to his abilities, but we are not inspired about workers’ rights, civil rights, or any of that messy stuff.

But it was an era, too, of messy stuff. What many may forget today, particularly if they are classic film buffs and have a rather sentimental view of American patriotism during World War II, is that we were really not unified up until Pearl Harbor and not even afterwards. People who lived during that time can tell you different, but we are losing more and more of the Greatest Generation every day, so intimate knowledge of those days is being lost, and their valuable ephemera—diaries, letters, oral histories—is often overshadowed by the more glamorous movies of the era which tell us everybody was on the same side.

Manufacturing, for instance, was not. There was great resistance to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s call for war production, especially by the car companies. What won them over was that the government promised them “cost-plus” contracts which meant that they would never lose money, they were guaranteed profits. So much for patriotism.

Today, we see the workers – not the management – of General Electric pushing for that company to shift to making ventilators for the COVID-19 crisis. They are demonstrating in plants in New York, Texas, Massachusetts, and Virginia to shift from making aircraft components, turbines and their normal production to medical equipment. Otherwise, GE is in the process of laying off thousands of its employees due to the current economic recession, which could find us in depression soon.

Though American manufacturing may have needed to be dragged to the war effort in World War II, nevertheless, manufacturing, in large measure, won the war. America and its allies would never have succeeded without the massive and vigorous juggernaut of American manufacturing. The car companies were a big part of that.

President Roosevelt’s wartime production policies were the basis of the 1950 War Production Act signed by President Harry Truman during the Korean War, and it is this act which Traitor Trump is being urged to fully implement to force General Motors to produce ventilators. So far, under pressure to use the DPA, he has signed an order for FEMA to acquire N95 masks from 3M.

When teaching history to children we must always emphasize that history is never just the past. It always shines a light on the present.

Nash-Kelvinator was formed in a merger in 1937 between the Nash Motors and Kelvinator Appliance Company. We may recall the Nash Rambler and the Kelvinator refrigerators. The company merged with Hudson Motor Car and the appliance division was later sold off to a company that would produce White-Westinghouse, Gibson, and Frigidaire products. The car division ultimately became American Motors Corporation.

I first discovered these ads as a child, probably at about 10 years old. In my elementary school classroom, there was a bookcase in the back of the room filled with old books and National Geographic magazines from the 1940s. I suppose they might have been donated. If we were done with our assignments and had some free time, we were allowed to take a book or magazine from the back of the room to our desks. I loved those magazines for the ads. I wasn’t too interested in the articles – world geography had changed quite a bit in the 1960s and early 1970s so that the social studies classes of my era bore little resemblance to the information in the old magazines – but World War II-centric ads were fascinating. They were even more educational. So much so that some years later when a librarian told me the town library was sending its old National Geographics to be bound into book volumes and tearing out the ads, I blurted, "They're the best part!" She looked at me like I had two heads.

They were like the old movies that I loved. They plunked you down into a specific moment in time. They were dramatic. They made you wonder.

They were like the old movies that I loved. They plunked you down into a specific moment in time. They were dramatic. They made you wonder.

*********

Jacqueline T. Lynch is the author of Ann Blyth: Actress. Singer. Star. and Memories in Our Time - Hollywood Mirrors and Mimics the Twentieth Century. Her newspaper column on classic films, Silver Screen, Golden Memories is syndicated nationally.

0 Yorumlar